Hhow to

Hhow to

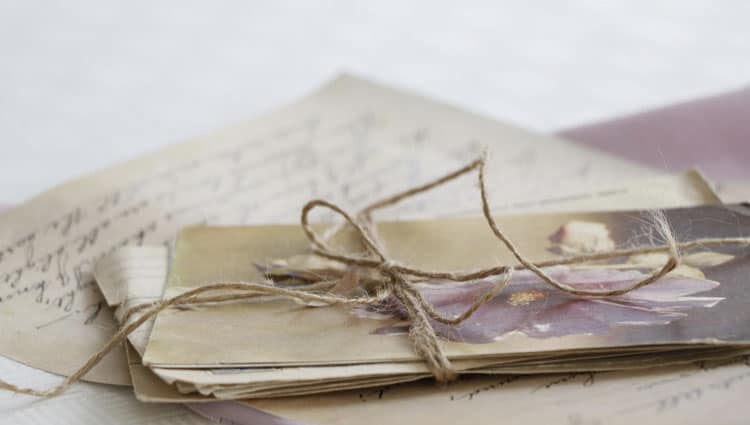

How to find and use ancestor writings for ancestry research.

In reviewing the writings of my Ancestors—whether they were letters, journals, postcards, notes, or email—I found interesting (and valuable) information, such as the following:

- Dates and places of events and experiences are essential in the writer’s life.

- Details of day-to-day life.

- Personal opinions and perspectives.

- Concerns and priorities.

- Thoughts and feelings.

- Hopes and dreams.

- Facts and dates about relatives and neighbors.

- Exciting views of historical happenings that were current events to them (wars, elections, epidemics, and so on).

- Background information about living conditions, prices, and other daily happenings.

How to Search, Find and Evaluate Ancestor Writings

Table of Contents

- Defining Ancestor Writings

- Before You Start Your Review Ancestor Writings

- Strategies for Interpreting Ancestor Writings

- Questions to Ask About Ancestor Writings

- Expanding on the Ancestor Writings

- Simplifying the Analysis of an Ancestor’s Writings

- Where to Search for Ancestor Writings

- Searching in Libraries and Archives for Ancestor Writings

- Digital Reproduction and Transcription

- Other Articles to Consider on BeginMyStory.com

The writings can be lively and full of energy—some fresh and intimate, some dull and non-descriptive, and most plainly spoken— simply sharing a moment in time, putting to paper something they felt needed to be said. I’ve found the documents in various places, including attics, closets, basements, bookshelves, in the homes of your known relatives, in possession of distant cousins located through research, and in libraries, archives, genealogical and historical societies, and other specialized collections. I have also found my Ancestors’ writings in antique shops, used book stores and flea markets—especially in places near the subject’s residence—and through websites designed to reunite diaries, photos, bibles, and other memorabilia with the families from which they were separated.

I have used the information to find dates of life events to further research; to find names of family members, neighbors, and others who interacted with the Family; to gain insight into the personality of the Ancestor; to put the Ancestor’s life into the context of time and history; to pull interesting details or excerpts for a Family or personal history, I am writing, and finding clues of medical conditions that may continue to affect Family today.

Defining Ancestor Writings

During my time as a historian, I have had the fortune to come across several artifacts from my Ancestors, including the letters and cards of my mother, journals and poetry of my father, and various bits and pieces shared by others. These combined artifacts begin to tell a story of a life that isn’t so different from my own. Before we progress too far, I would like to outline some of the differences you will find in written communications.

Letter

A letter is a direct, written message usually sent some distance from one person to another, or even to a group of persons or an organization. Some of the earliest recorded letters were written about 3500 BC by the Sumerians (using picture writing), who wrote on clay tablets using long reads.

An old term for the letter is “epistle,” from the Greek word epistle, meaning “message.” Several books of the bible are made up of letters.

Letters are a dialogue between parties and often become objects to represent the absent person’s touch and nearness. Nathaniel Hawthorne became a famous author, but he spoke like countless other correspondents when he wrote to his sweetheart Sophia Pea- body in 1840, stating, “The only ray of light” in his dreary day “was when [I] opened thy letter. . . . I have folded it to my heart, and ever and anon it sends a thrill through me. . . . It seems as if thy head were leaning against my breast.”

Some letters are scattered and must be gathered to form a collection of writings.

Nowadays, letters are only widely used by companies who send out these mailings to many people (who may not have access to the Internet for email).

The term “letter” is sometimes used for email messages with a formal, letter-like format.

Journals and Diaries

In 1656, John Beadle, an Essex minister, wrote an advice manual on keeping a diary and explained the variety of types written in the seventeenth century. He said:

We have our state journals relating to national affairs. Tradesmen keep their shop books. Merchants their account books. Lawyers have their books of pre[c]edents. Physitians have their experiments. Some wary husbands have kept a diary of daily disbursements. Travellers a Journall of all that they have seen and hath befallen them in their way. A Christian that would be more exact hath more need and may reap much more good by such a journal as this. We are all but stewards, factors here, and must give a strict account in that great day to the high Lord of all our wayes, and of all his wayes towards us.

The terms “journal” and “diary” are used interchangeably today. No matter what you call them, these accounts are the autobiographies of ordinary people like our Ancestors, and these may be the only existing records of their personal lives. In addition to historical data, diaries give us a glimpse into someone’s daily life, thoughts, and attitudes. A diarist may also record feelings on national events, such as a war or its impact on Family and the community. The following is an attempt to define meanings as used over the last several centuries.

Diaries (the private journal)

Some use the words “diary” and “journal” interchangeably, while others apply strict differences to journals and diaries: dated, undated, inner focused, outer focused, forced, and so on. The following are a few points to remember:

- Diary is referred to as a private journal.

- The current preference (based on book and article titles) is to use “journal.” The phrase ” journaling” is often used to describe such hobby writing, similar to “scrapbooking.”

- Diaries are relatively recent, from the 1700s in the culture of Western Europe and early America.

- The popularity of diaries stems from the Christian desire to chart one’s spiritual progression toward God.

- Expanded in the 1800s to record personal feelings, self-discovery, and self-reflection.

- Diaries are found in all aspects of human life, governmental, business ledgers, and military records. Diaries run the spectrum from business notations to listings of weather and daily personal events to inner exploration of the psyche, or a place to express one’s deepest self.

- Diaries or journals are often written to oneself or an imaginary person. It may resemble a letter to one’s self.

- There is a strong psychological effect of having an audience for one’s self-expression, a personal space, or a “listener,” even if the “audience” is the book one writes in, only read by oneself.

- Some diarists think of their diaries as special friends, even going so far as to name them. For example, Anne Frank called her diary “Kitty.”

- A single individual between its covers usually weaves together a diary.

- A well-known example is “The Diary of Anne Frank,” whose diary chronicled the desperation of being Jewish in Amsterdam during World War II and having to go into hiding from the Nazis. First, the diary is a day-by-day account of the life of a Jewish Family and their friends. Secondly, it is a biting commentary of the depths of suffering men can impose on other men. A stunning website about this child and her story is at http://www.annefrank.com.

Journal (public record)

A journal (French from late Latin diurnal, “daily”) has several related meanings:

- A daily record of events or business; a private journal is usually a diary.

- A newspaper or other periodical, in the literal sense of one published each day; however, some publications issued at stated intervals—such as a magazine or the record of the transactions of society such as a scientific journal or academic journals in general—are called a journal. “Journal,” then, is sometimes used as a synonym for “magazine.”

- The word “journalist” (for one whose business is writing for the public press) has been used since the end of the seventeenth century.

- Section 5 of Article I of the United States Constitution requires the Congress of the United States to keep a journal of its proceedings. This journal, the Congressional Record, is published by the Government Printing Office. Journals of this sort are also often referred to as minutes.

- A book in which an account of transactions is kept previous to a transfer to the ledger in the process of bookkeeping. For example:

- A central book in which all financial transactions were recorded. These include the purchase of supplies, the sale of crops, the purchase and sale of livestock, and the purchase, sale, birth, marriage and death of enslaved people, apprentices and other servants;

- The record of all agricultural activities from year to year, including the purchase of seed, fertilizer, cordage and wire, plows and other equipment, cost of labor, places of sale, transportation costs, and the prices obtained for the crops; or

- A chronicle of life on the farm, including some or all of the above. Journals can provide essential clues to African-American Genealogists researching their slave Ancestors. Plantation records may be the only Place to ascertain names and dates necessary to prove ancestral ties.

- An equivalent to a ship’s log—as a record of the daily run— such as observations, weather changes, or other events of daily importance.

Postcard

A postcard is typically a rectangular piece of thick paper or thin cardboard intended for writing and mailing without an envelope and at a lower rate than a letter.

The United States Postal Service began issuing pre-stamped postal cards in 1873. Postcards came about because the public was looking for an easier way to send quick notes. Postcards were very popular in the early 1900s. For example, in 1908, more than 677 million postcards were mailed.

The messages contained in postcards are necessarily brief and generally lighthearted, as the sender is generally on holiday and switched off from the day-to-day routines of home and work.

Greeting Card

A greeting card is an illustrated, folded card, usually featuring a greeting message or another sentiment.

The oldest known greeting card is a Valentine made in the 1400s and is in the British Museum. New Year’s cards can be dated back to this period, but the New Year greeting didn’t gain popularity until the late 1700s. Cards gained their highest popularity in the late 1800s and early 1900s, offering cards with some of the most unusual art.

Greeting cards are usually given on special occasions such as birthdays, Christmas, or other holidays, but they are also sent on “non-occasions” to say hello or thank you. Ninety percent of all paper greeting cards are sold in the United States.

Greeting cards, usually packaged with an envelope, come in various styles. They are manufactured or handmade by hundreds of companies, big and small.

Card inscriptions can be windows to how an Ancestor felt about the recipient. A card is often a token of affection that articulates the form of love and affiliation of a given period. The messages in greeting cards are usually brief, and mostly the sender confines himself to the brevity that the form imposes, and the message is cheerful and upbeat.

Written Note or Message

These types of messages range from a piece of paper tucked into a journal as a personal reminder to a note in the margins of a letter denoting an extra add-on thought.

Written notes can provide insight and extra meaning to what has already been written.

Electronic mail, now usually called “email,” is a method of composing, sending, storing, and receiving messages over electronic communication systems.

Email started in 1965 as a way for multiple users of a timesharing mainframe computer to communicate.

Blog

A weblog, usually shortened to “blog,” is a website where regular entries are made (such as in a journal or diary) and presented in reverse chronological order. Blogs often offer commentary or news on a particular subject, such as food, politics, or local news. Some function as more personal online diaries. A typical blog combines text, images, and links to other blogs, websites, and media related to its topic.

Before You Start Your Review Ancestor Writings

Whether you are reviewing a private collection handed down from Mom or one you find in university archives, the following are a few questions and ideas to consider:

- Is this volume the complete diary, or are there other volumes or entries elsewhere?

- Is this letter a draft or “practice” letter, or is it the one actually mailed?

- Who saved the diary and why?

- Who collected the letters and why?

- Is there evidence of other readers (Family members, archivists) handling or marking the text?

- Has the diarist herself added retrospective marginal notes? (Many diarists look back and criticize their younger selves or annotate their observations, scratch out passages, or even cut out pages.)

- What is the period covered by the text? Plan your reading to quickly scan the pages ahead to see if the number of diary entries (or letters) changes because of major historical events.

- Does the diarist clearly distinguish one day from another?

- How frequent are the entries? In one Family collection, I found several hundred postcards that covered thirty years between Family and friends. Yet in another, I found 300 separate journal entries in six months during the waning months of an individual’s life.

- It is also worth a quick look ahead to see if one correspondent’s letters dominate the collection or if the letters are more like a dialogue or even an entire conversation among many people.

- Check out event changes, such as where the communication was written. Often a writer will indicate when they are writing (such as Munich, Germany, or Lawrenceville, Georgia).

- Look through the collection to see if there are indications of important events. For instance, during the 19th century, deaths often were written on black-edged paper; letters announcing a marriage tend to be embossed or differently sized—both easy to spot in a sheaf of papers.

Strategies for Interpreting Ancestor Writings

Whether you are reviewing a letter, journal, postcard, or other writing of an Ancestor, there are several strategies for evaluating and gaining the most from the entire presentation. Not only are you looking at the written word, but you are also looking at paper, images, and handwriting, and all provide clues and information about your Ancestor. The following represents different angles from which to view the writings of your Ancestors.

Impressions by look and feel. As you hold the writings in your hands, they make an impression before you even read the words. You can glean information from the texture, condition, paper type, style of writing—which suggests the writer’s care or haste—depth, surface, care of the folded sheets of a letter or the binding of the diary, and the time between inscriptions. The following clues can help you begin to make guesses about the writer, such as what their social class might have been:

- Is the paper the ordinary lined “blue” sheets of everyday mid-nineteenth century use, or is it embossed and edged?

- Women and men were schooled to have very different handwriting.

- The document might exhibit an array of nibs (the sharpened point of a quill pen; a pen point), papers, envelopes, letter cases, letter clips, writing desks, and other objects associated with writing among well-to-do Americans of the era. The absence of these features may indicate that the writer was of lower economic standing.

Think in terms of plot, characters, and language of the script. Think of the last article, story, or even movie you watched. Who was the main character, and who were the subordinate characters? What was the plot? How was the script written? As you review writings, you gain a feel for the individuals involved, their roles, and the plot’s events.

Becoming acquainted with the characters. In a diary, we depend on the writer to introduce us to the individuals in their life. Sometimes persons are named, while other times we are left to figure them out for ourselves. When it comes to letters, the introductions to characters are hit and miss. The writer wasn’t writing to us, but usually, one who knew the people mentioned.

Try to understand who the friends and family members were, primarily if you use unedited communications. Sometimes a Family rarely uses given names in correspondence. In such cases, start slow until you can determine the identity of “Dear Son” or “Your loving Daughter.” The same holds for nicknames.

What inspired the plot?

As you survey the writing, think about whether a particular circumstance inspired the writing. Is there a large-scale “story” holding the writings together? We find this type of inspiration in writings during war or changes in one’s life. In other cases, diaries—and especially letters—are focused on the ordinariness of the writer’s life. In either case, though, surveying the text for a sense of the main narrative thread is an excellent way to prompt questions about the text as you begin to read more closely.

Look for a unique language

Think about your use of instant messaging. We use words, phrases, and acronyms to help us communicate faster in our writing. For example, 🙂 (smile), K (okay), TTYL (talk to you later), TY (thank you), and Ditto (I agree).

Just like us, our Ancestors also had interjections into their correspondence that stood for something else. For instance, many modern readers are puzzled by some correspondents’ interjection of “D.V.” amid specific sentences expressing hope (“by now, D.V., you are safely at home”) when these letters are not the recipient’s initials. Then, finally, one writer solves the puzzle for us by spelling it out: Deo Volente, “God willing.”

Such puzzles will help you to be alert to the fact that the meaning of certain words or phrases is coded. For example, to say in the mid-nineteenth century that a woman had “taken a cold” almost always meant that she was pregnant.

How does the writer relate the experiences of their life? Personal texts are usually begun by the accounts of critical events that occur over time and are important enough to write about, such as a death, a child leaving home, a marriage, a natural disaster, work, and so forth.

The story of events also reveals the interrelationships of the writers, friends, Family, acquaintances, and strangers. The relationships shape our understanding of how the writer fits into the events and through which eye we see the interpretation of what is written.

Most letters are written by “news” or are rich with events, which the writer tries to describe in detail. You may see how the writer describes (or filters) the same event or news to different people in his life. For example, an experience about crossing a river and almost drowning may be written in full detail for a friend, but to a mother, the description may be only that the writer became wet when crossing a river.

In letters, you will find other parties sensitive to the absence of one another. Some, however, focus on the distance apart. In contrast, other letters focus on bringing one closer together—such as in the case of lovers or parents and children blaming each other for neglect or praising each other for timely and satisfying letters.

Questions to Ask About Ancestor Writings

As you review Ancestors’ writings, don’t conduct an in-depth analysis of every word, sentence, or meaning in every artifact. To examine the artifacts by carefully identifying and analyzing the items. Then reflect on what you’ve learned.

Identify

Ask yourself about the primary source itself:

- What do I have (e.g., letter, greeting card)?

- Who created the writing?

- When and where was the writing created?

- What’s the history of the writing?

Analysis

Ask yourself the following questions about the primary source:

- Creator

-

- Who created the primary source and why?

- What was this person’s role in the event, period, or activity?

- What was the person’s perspective, point of view, opinions, interests, or motivation? How did this impact the content?

- What was the purpose for developing the writing?

- Was the writing intended to be public or private?

- Was the intention of the creator to inform, instruct, persuade, or deceive? How did this impact the content?

- Which events—trivial or monumental—do Ancestors choose to share?

- Are any events or topics ignored or skirted?

- Who among the correspondents seems the most intimate, and who seems most at odds?

- How does each writer seem to value formal respect and careful language, on the one hand, and humor, exaggeration, and slang, on the other?

- Does one individual seem to be the central person in the correspondence, and, conversely, is there an individual everyone seems to regard as shy or silent?

- Which relationships seem most stable throughout the correspondence and most volatile, and how do events in their lives reveal these qualities?

- How do all of these relate to the identities of the various correspondents in terms of gender, class, or age?

- Timing

-

- Was the item created before, during, or after an event?

- How might the timing of the creation impact the emo¬tions, accuracy, or perspective?

- Setting

-

- What is the setting of the primary source? Where was it created?

- What were the conditions or circumstances related to the creation?

- What information (such as facts and opinions) does the primary source contain?

- What could details easily be misunderstood?

- How does this resource compare to other information from the event or period?

- Visual information

-

- What story does the image tell?

- What is the perspective or point of view of the image?

- What is the setting of the image?

- What details are emphasized or missing?

- Just for the diary and journal

- Who is the “other” the diarist seems to be writing to a friend, a wiser self, a future self?

- What other literary forms does a given diary most resemble—a letter, a novel, a ledger?

- What kinds of events, times of the day or week, and emotional state motivate the diarist to write?

- Does the diarist always write in the first person, or does he sometimes distance himself by avoiding the “I”?

- Which people in the diarist’s life appear most frequently in their pages, and why?

- Do any or all of these features of a given diary change over its course, and if so, in what way?

- Reflection upon findings

- Ask yourself the following questions about your findings:

- What information was fascinating or surprising? What would be interesting to investigate further?

- What questions do you have about the information? How could they be addressed?

- What inconsistencies or conflicting ideas did you identify? How could they be resolved?

- How does this document connect to your life? What are the relevant issues for today?

Expanding on the Ancestor Writings

Writers will often make assertions about a fact that was important to them. For example, a correspondent mentions the death of a loved one due to the flu epidemic in 1917. It might be vital for you to consult other sources that describe the extent of the flu in that town, state, or country. Or suppose a diarist makes a claim about a visit of President Kennedy on January 15, 1961. In that case, one could consult official documents, newspapers, and other observers to give perspective to what the diarist says.

Depending upon how wide you want to take your study, you can include many sources, such as census reports, government documents, photographs, maps, oral histories and other diaries and letters. For example, I read in several journals and histories that my Ancestors were cattle ranchers in Utah County, Utah. I am from the city and have no clue about cattle ranching. I took the opportunity to find newspaper articles about ranching in Utah. I checked the Utah State Government Brands & Animal Identification Department to find if they had a brand. I looked for photos from the early 1900s of cattle ranching in Utah and anything else I could find that would help me understand this profession related to Utah ranchers. Now, as I write about my great-grandfather, I can better explain and provide details about what their lives as ranchers might have been like, the jobs they performed, the trials they endured, and the satisfaction they may have felt.

The following are other ideas to use:

Chronology

Build a timeline associated with the item. In addition, create a parallel timeline that relates related, national, and international events. Also, consider tracing the Genealogy of the families associated with the item. Use this chronology to help develop an understanding of the period.

Maps

Explore the locations discussed in the document. Consider is visually tracing adventures and activities. Use maps to help develop a context for the Place associated with your project.

Relationships

Explore the relationships among the people represented in the document.

Visual resources

Match visuals (such as photographs) to the document’s people, places, and events.

Multimedia resources

Consider connecting the arts, books, music, movies, and other activities to the resource.

A couple of things happen when you seek to corroborate and add context to the story. You expand the “what happened” and have a more remarkable ability to interpret what you are reading from their viewpoint. You also understand how accurate the writer was in interpreting their times as an actor and observers.

Return to Ancestor Writings Table of Contents

Simplifying the Analysis of an Ancestor’s Writings

It’s an excellent opportunity to evaluate and become acquainted with Ancestors through their writings. Some Genealogists want to find the facts and not spend much time analyzing. The following is a simplified process for reviewing an Ancestor’s writings:

- Identify factual information. (How is the writing, about what, and where?)

- Who are the main characters described in the letter?

- What is the plot of the letter?

- What questions do you have about the artifact? Include words you can’t decode or understand.

- What research would you need to do to widen your understanding of the letter?

Where to Search for Ancestor Writings

Getting access to Ancestors’ writings that have others. These Ancestors’ journals, letters, and writings are very precious to those who own them. The owner’s response to your request to access them depends a lot on how well you know each other. If they know and trust you, they may allow you to take the documents on loan for a specific period—usually 24 to 48 hours—to scan or photograph the article.

In cases where information is a little more challenging to secure, consider the following approaches:

The insurance copy argument

If they have the original item, remind them that it could be lost or gone forever in a house fire or other disaster; by letting you copy it, the Family gains a backup, security, or insurance copy.

Broker

Offer to make them a copy when you make a copy.

Trade

Offer to exchange copies of records or items that you have in return for them letting you copy their materials.

Family project

Design a Family project—biography, photo collection, newsletter—you need to copy and use their materials. This links your request to a Family cause rather than just being personal.

Purchase

If the person’s reluctance to share is because of the monetary value of the items, consider buying the material, or at least a part of it.

Take pictures

They might have an heirloom locket or Civil War uniform or other valuable items they won’t let out the door. In such cases, take pictures of them and offer to share copies of your photos.

Searching the internet for ancestors’ writings

The Internet is an incredible resource in finding diaries, journals, postcards, letters, and other writings. I have found Family documents on Internet sites of library collections. For example, as I was doing research for a presentation, I found thirty letters written between Thomas Jefferson and my Ancestors in the Jefferson Papers and fifteen journal entries relating to my Ancestors’ pioneer experiences in the Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel, 1847-1868 collection.

To search the Internet for ancestral writings, enter the following information:

- Names of Ancestors (direct and collateral lines)

- Surnames (include various spellings)

- Names of individuals the Ancestors were known to have worked with or had relationships with

- Places they lived and visited

- Important events they lived during or were a part of, such as the civil war, influenza, or pioneer treks

A note about spellings

You will find that spelling was informal and inconsistent in old records. Do not dismiss the name ‘Hewes’ if you are searching for ‘Hughes.’ In an early census enumeration, census takers reportedly spelled the surname ‘Reynolds’ in thirty-four different ways. As you get deeper into genealogical research, you will become an expert at guessing how many ways a name may be spelled (or misspelled).

Examples of search strategies.

Keyword searches

- diar* and literature [will retrieve ‘diary’, ‘diaries’, and so on]

- diar* and bibliography

- Virginia and diaries [for locating many individual

- diar* and statesm*n

- memoirs and wom*n

Subject searches

- American diaries women authors

- Women United States diaries

- Women diaries

- English diaries

- Personal narratives [relating to individual events or periods]

Searching in Libraries and Archives for Ancestor Writings

I have found journals, diaries, and letters that have been preserved in local historical societies, universities, and other institutions where they are available to researchers. Some have been published as books, and increasingly many are available on the Internet. An excellent place to start is searching for writings in the areas where your family lived.

One historian told of an experience where she found an Ancestor’s diary (who lived in Virginia) in New Mexico. The descendant who inherited the diary lived in New Mexico and gave it to a repository.

What to do when you still can’t find the written word of your Ancestor. My mother passed away in 1997, and I realized there was a lot I didn’t know about her. I began to interview their family and friends to gain her insights. To my joy, many of these people had kept letters, greeting cards, and postcards that she had sent them throughout her life. The information provided insights into her children’s feelings and her pains, joys, and desires. I was allowed to scan and photograph these documents.

Strategy 1: Your first option is to contact all of your relatives and see if they saved the writings of Ancestors with whom your family may have had a relationship. Letters and diaries written by your Ancestor’s relatives, friends, and neighbors may contain material about your Ancestor. These letters and diaries will give you a glimpse into what your own Ancestor’s life was probably like since relatives, friends, and neighbors probably came from the same socioeconomic background as your Ancestor.

Several of my ancestors were Mormon pioneers in the mid- 1800s. Although there are no surviving journals from my Family of this period, I have found journals of people who were part of the same wagon train or handcart company. I have been able to review these writings and better understand what my Ancestor may have experienced. I found an entry about my progenitor from the Dan Jones Emigrating Company, Journal 1856 May-Dec.

September 9, 1856

Tuesday 9th[.] The remaining Waggons taken over the river [.] finished at 2 p.m. A yoke of Oxen belonging to the Church was missing. several brethren sent to search for them, and they returned to camp with them at 4.15 p.m. Bro. Elias Jones lost two gentle Cows on Sunday last <at the Loop [Loup] Fork Ferry>, and up to this time, they have not been found. We moved forward at 5 p.m. and camped at 8 p.m[.] traveled 7 miles along the banks of the Loup Fork.

Strategy 2: Look for writings that discuss the same time, event, and so forth. Circumstances similar to theirs may be available in a personal account written by another person from the same area. If you can find a relationship, either through bloodlines or common bonds, you’ll discover a way to understand and add depth to your Family’s history. Look for similarities in lifestyle, social status, profession, or neighborhood. All of these can give you a good sense of how your ancestors lived and what they experienced.

Strategy 3: Place a query online or in a genealogical magazine or message board to see if some distant relative might have an Ancestor’s writings. On one occasion, I received a clue about a letter from a relative in 1862. I had seen the text—a photocopy of photocopies—but I wanted to see the original. I placed a query on the message boards and, in time, received a clue of where to go. I eventually found the owner and was able to get a photograph of the letter.

Summary checklist: Where to search for Ancestors’ writings. The following is a recap of where to search for writings (diaries, journals, letters, or postcards) of your Ancestors:

- Ask relatives if they possess any Ancestors’ writings.

- Put queries in genealogical magazines, message boards, and online, seeking writings from distant “Genealogy” cousins.

- Write to historical societies, archives, and libraries in your Ancestor’s locality to see if your Ancestor’s writings were deposited there.

- Check reference guides to help locate writings in repositories.

- Look for published writings, including anthologies.

- Look for the writings of your Ancestor’s friends, relatives, and neighbors.

- Look for writings of people, like your Ancestor, who lived in the same geographic area during the same period and from the same socioeconomic background.

Digital Reproduction and Transcription

As you review the writings of your Ancestors, you will most likely want to transcribe the information, making it easier to read and use in multiple formats when sharing on the Internet and with others. I have found artifacts such as diaries, journals, and letters to be very fragile; it seems as though the glue, string, and paper are disintegrating before my eyes. I prefer not to work with the origi¬nal when I transcribe (keeping the original safe from becoming any more worn), but rather work with digital reproduction.

Digital reproduction. A digital reproduction is an electronic version of an artifact created using a scanner or digital camera.

When you are creating a digital reproduction, you will either want to reproduce the artifact—including matching colors, shading, and flaws—or have the intention to maximize the legibility of the item. I lean toward the side of digital reproduction for legibility while trying to preserve as much of the original. I will usu¬ally keep what I call my original file, which is the exact image of the original, and then I have the edited file, which is the original with my desired edits.

I use Adobe Photoshop Elements as my image editing software. It allows me to adjust the contrast, color, and sharpness of an image, and I can edit out perceived flaws, creases, discoloration, water stains, or missing pieces.

Beginning your transcription project. Before beginning your transcription project, it is essential to gather basic information that will later form the description paragraph or introduction to help others understand the project.

Provide an introduction to the project, consisting of the following elements:

- Identification: Provide background information about the project, including the format, length, and other physical attributes.

- Documentation of the history: Discuss the origin of the document and trace the history.

- Strengths and weaknesses: Note strengths or the project’s unique nature, along with problems encountered or concerns about accuracy or authenticity.

- Acknowledgments: Include credit and history of document ownership and credit for digital transcription and reproduction.

Editorial transcription guidelines

Transcription is the conversion of one form of language into another, such as handwritten letters into typewritten documents. As you begin to transcribe your documents, the following set of editorial guidelines will help you maintain consistency:

- No attempt should be made to correct spelling or perceived “mistakes.”

- Avoid capital letters except in those instances where the writer used a capital letter.

- Make educated guesses when unsure of a word; however, use square brackets [] when unsure of exact transcription. If you cannot decipher the words, then use brackets and a note such as [illegible]. Some people choose to use colors for particular notations in a digital format.

- Whenever possible, match the punctuation used by the author. Or you can standardize the punctuation. For example, you may choose to use commas and periods for dashes, vertical strokes, or other markings.

- You may or may not choose to maintain the document’s formatting, such as line breaks.

- Sometimes areas of a document are illegible. Use the following strategies to help with complex materials:

- Examine individual letters and match them to other areas of the text.

- Scan the document at a high resolution and zoom in electronically.

- Read the sentence aloud and look for context and logical connections.

- Ask someone else to read the passage.

- Do not assume you know what the words or letters are.

- Leave the passage and come back later with a clear mind.

- If you still can’t figure it out, take your best guess and put it in brackets.

The following are the personal guidelines I adopted to create a transcript from the Ohio Memory Project:

- Create a new document in a program such as Microsoft Word, Edit Pad, or Word Pad.

- When sharing with others, save the document as ASCII or text only (.txt).

- At the top of the page, type [page 1]

-

- If the first page included is not the first page of the book or document, add a second line, such as [corresponds to page 456 of John Jones’ Diary].

- Hit “return” or “enter” twice to place a blank line between the page information and the beginning of the next page

- Copy text from the first page of the document. It is important to remember that you are creating an exact copy of the original document in typed form, not editing or interpreting the original. Each transcript line should follow precisely the spacing and line breaks in the original document, even if a sentence or thought ends after a line break.

- Hit return twice after each line in the original to insert a blank line between the lines of text. This maintains the line breaks even if the document’s font size gets changed. Do not select double-spacing from the formatting menu. Add comments in brackets (sparingly) to describe notes or scribbles that cannot be translated. Appropriate uses of comments include the following guidelines:

- If a document has numerous pencil scribbles, type [numerous pencil scribbles] near the area where they occur on the page.

- If a word is illegible, type [illegible] in square brackets. Do this even if you can guess at part of the word.

- If text is otherwise unusual, indicate how with such notes as [crossed out words], [on back of letter], [written in pencil].

- If there is a misspelling in the original, the transcript should include the same misspelling. Make sure to turn off any auto-correct options in your word processor.

- Following the last word or comment from page 1, type [page 2], hit return twice and type text from the second page. Repeat for remaining pages, but keep pages together in one document.

- A good transcript should follow the same form as the writ¬ten page; the same words should be on the same lines in both the transcript and original document. Here is an example of how transcription from an original document looks:

[Page 1]

[corresponds to page 1 of Cleveland Ordinance Banning Baseball]

An Ordinance [underlined]

For the protection of the Public Ground

Be it ordained [Be . . . ordained underlined] by the City Council of

Cleveland that from and after this date it

Shall be unlawful for any person or

Persons to play at any game of Ball

Or at any other game or pastime [illegible]

the grass or grounds of any

Public Place or square shall be deface or

Injured, and any person or persons

who may be convicted of any of the

above offences before the Mayor shall

forefiet and pay to cit any sum

not less than five dollars at the [caret mark] discretion of the

[above caret mark (Word insertion)] Mayor with the cost of

prosecution

Passed Mch 5/45

Attest J.B. [Illegible]

W [illegible] Goodwin

City Clerk Signed Alderman

Interpreting the handwriting of your Ancestors

Little time will be spent discussing interpreting handwriting other than to say that learning to read your Ancestor’s handwriting is an important skill to have. One resource I have referred to and find to be outstanding is Reading Early American Handwriting by Kip Sperry. This book is designed to teach you how to read and understand the handwriting found in documents commonly used in genealogical research.

Other Articles to Consider on BeginMyStory.com

- How to Search, Find and Evaluate Ancestor Writings

- 7 Writing Styles to Use When Composing Your Journal

- 4 Tips to Decode the Meaning of Ancestor Writings

- 11 Creative Ways to Record Your Life in A Journal

- 7 Tips to Reading Abbreviations in Ancestor Writings

- 6 Tips on How to Read and Understand Ancestor Handwriting Styles

- Where to Search for Your Ancestors’ Writings

- 5 Strategies for Interpreting Ancestor Writings

- Questions to Ask As You Review Writings of Your Ancestors

- Search for 9 Types of Ancestor Writings

- Expanding on the Writings of Your Ancestors

- Other Free Resources: Archive.gov, FamilySearch.org

Sources

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/letters/question3.html

https://escrapbooking.com/primarysources/interpretation.htm